by Rabbi Mordecai Griffin

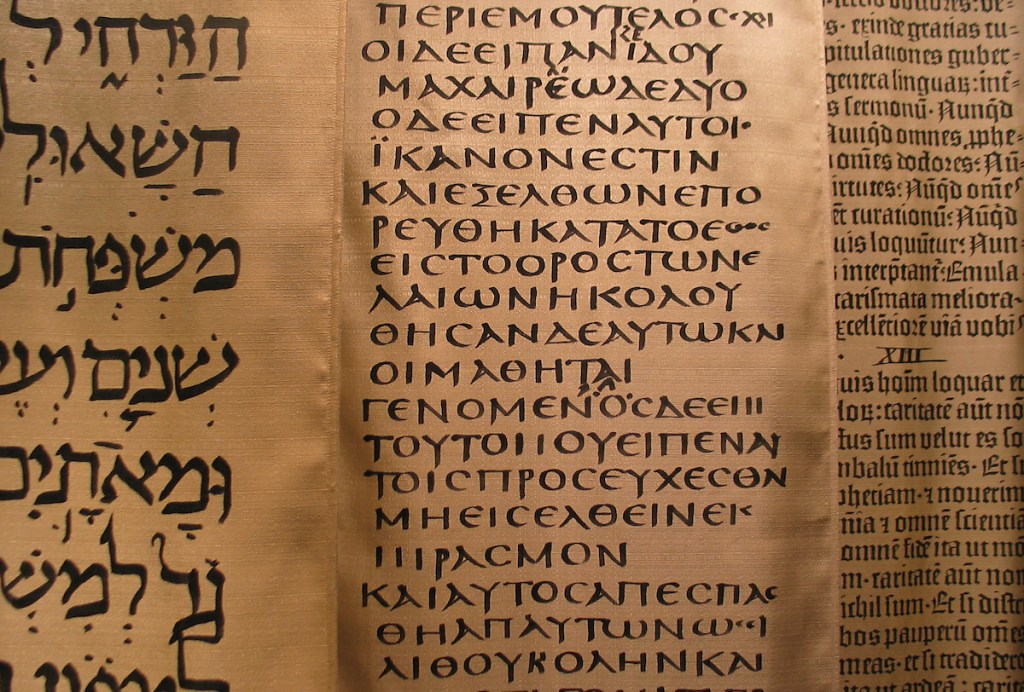

The Septuagint: A Jewish Translation, Not a Christian Construct

On December 7, 2025, at the Heichal Shlomo Jewish Heritage Center in Jerusalem, Rabbi Tovia Singer—widely known for his role in contemporary Jewish anti-missionary apologetics—participated in a public debate with a Christian pastor from Australia. As expected, the discussion centered on whether Jesus of Nazareth fulfills the messianic expectations of the Hebrew Bible. As the exchange progressed, particular attention was given to several familiar texts—Psalm 22, Isaiah 7:14, and Isaiah 9:6—passages whose wording differs in meaningful ways between the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) and the ancient Greek Septuagint (LXX).

It was at this point that Rabbi Singer made a categorical statement upon which he appeared to place the entire debate:

“I want to make a statement here, and I want to be very clear. If the Septuagint is the word of God, then I concede this entire debate.”

The force of this remark should not be understated. Rabbi Singer was not merely questioning the interpretive value of the Septuagint; he was denying its theological legitimacy altogether. The implication was clear: the Septuagint—particularly beyond the Pentateuch—was not a faithful Jewish translation of Scripture but a later Christian construct, unworthy of being regarded as the Word of God.

To support this conclusion, Rabbi Singer asserted that only the Torah was translated into Greek by Jewish scholars, while the remainder of the Greek Bible—especially the Prophets—was allegedly a later Christian creation, commonly attributed to Origen and his third-century work, the Hexapla.

This claim is not merely controversial. It is historically indefensible.

The Septuagint and Historical Reality

No serious Jewish, Christian, or secular historian of the Bible holds this position. The evidence against it is extensive, coherent, and has been firmly established for more than a century. The Septuagint is neither a monolithic translation produced at a single moment nor a Christian fabrication retrojected into Jewish antiquity. Rather, it is a collection of Greek translations of Hebrew Scripture produced by Jews, for Jews, primarily in Alexandria, Egypt, between the third and second centuries BCE—long before Christianity existed.

The Letter of Aristeas and the Translation of the Torah

The confusion often begins with the Letter of Aristeas, which describes the translation of the Torah into Greek during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus in the third century BCE. Crucially, this account speaks only of the Pentateuch. It makes no claim whatsoever regarding the Prophets or the Writings.

Modern scholarship is unanimous: while the Torah was translated first, the Prophets—Isaiah included—were translated later, likely between 200 and 150 BCE, by different Jewish translators whose identities are now unknown. Linguistic analysis of the Greek confirms this chronology, as the translation style of Isaiah differs markedly from that of the Pentateuch, indicating independent Jewish translators working within a Jewish interpretive framework.

Pre-Christian Evidence for the Greek Prophets

There is overwhelming chronological evidence that Greek translations of the Prophets existed well before the rise of Christianity. Greek biblical fragments consistent with Septuagintal translation techniques have been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls and date to the first century BCE. These discoveries demonstrate conclusively that Greek Scripture circulated within Jewish communities prior to the time of Yeshua.

Jewish authors such as Philo of Alexandria and Josephus refer to the Greek Scriptures as a Jewish possession and show no awareness of Christian involvement—because none existed.

Christian Sources That Refute Christian Invention

Ironically, early Christian writers themselves refute the claim that Christians created the Septuagint. Justin Martyr, Origen, and Jerome all describe the Septuagint as a Jewish translation inherited by the Church.

Origen’s Hexapla was not a Christian rewrite of Scripture but a massive scholarly comparison placing the Hebrew text alongside multiple Greek translations—most of them explicitly Jewish, including Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion. The Septuagint appears in the Hexapla as a received ancient Jewish text, not as Origen’s creation.

Jerome explicitly attributes differences between the Hebrew and Greek to ancient Jewish translators, never to Christian authorship.

Internal Evidence of Jewish Authorship

The internal character of the Septuagint further confirms its Jewish origin. In numerous cases, the LXX weakens later Christian theological arguments by softening anthropomorphic descriptions of God, diminishing certain messianic readings, and preserving renderings that Christians themselves later found problematic.

No Christian translator would deliberately undermine texts such as Genesis 49:10, Isaiah 53, Psalm 2, or Zechariah 12:10 in precisely the ways the Septuagint does. These features reflect Jewish exegetical concerns of the Hellenistic period, not Christian theology.

Why Judaism Later Distanced Itself from the Septuagint

The later Jewish abandonment of the Septuagint is well understood and does not imply Christian corruption. As Christianity increasingly employed the Greek Scriptures in polemical contexts, Jewish sages in the second century CE moved toward standardizing a Hebrew textual tradition and commissioned new Greek translations, most notably that of Aquila.

The Septuagint gradually became culturally associated with Christianity—not because Christians authored it, but because they preserved it. Preservation, however, is not authorship.

Translation and the Word of God

Rabbi Singer’s concession rests on an unstated premise: that the Septuagint cannot be the Word of God because it is allegedly not Jewish in origin or faithful in transmission. Yet both premises collapse under historical scrutiny.

If the Hebrew Scriptures are the Word of God, and if the Septuagint is a Jewish translation of those Scriptures produced within Second Temple Judaism, then the Septuagint is necessarily the Word of God in translation. This conclusion does not depend on Christian theology; it follows directly from Jewish historical reality.

Judaism has never held that divine revelation is nullified by translation. The Aramaic Targumim—used publicly in synagogue worship—were often interpretive, yet long regarded as authoritative conveyors of sacred meaning. Translation does not negate sanctity; it mediates it.

Conclusion

In sum, the Septuagint—Torah, Prophets, and Writings alike—is a Jewish translation tradition rooted firmly in pre-Christian Judaism and frequently preserving Hebrew textual forms older than the Masoretic Text itself, as confirmed by the Dead Sea Scrolls.

To claim otherwise is not an alternative scholarly position but a rejection of established textual scholarship. Whatever one’s theological conclusions regarding messianic interpretation, honest debate requires fidelity to historical fact. On this point, the evidence is unequivocal: The Septuagint was a Jewish work, produced by Jews, for Jews, centuries before the Church ever existed.

Leave a comment